ERI supported the national university's emergent research project on this eruption, serving observation equipment, securing travel expenses for researchers, establishing emergent observation system, making applications for observation researches to the Ministry of Education, and so on. ERI itself organized the examination committee for maintaining its functions in emergent events, and set the steering office for the Usu eruption on March 30, a day before the eruption. The office gathered information related to the eruptive activity and provided it inside and outside the institute, and, as the cooperative research center of national universities, made communication and negotiation with the outside. Homepage of Usu eruption in the ERI server functioned effectively to distribute information on the research activity outside. Apart from the researches, ERI loaned four satellite telemetry systems to Japan Meteorological Agency for monitoring the eruptive activity, and dispatched technicians to install them.

Seismic and tilt observation: We have conducted broadband seismic observation at Usu volcano since just before the first eruption on March 31, 2000 in cooperation with other universities. In the broadband seismic observations, 13 broadband sensors were installed with continuous recording mode. Spectral analysis of the broadband data revealed the existence of very-long-period seismic tremor with dominant period longer than 10 sec, which cannot be detected by conventional short-period seismometer (for details, see 5-6 Broadband seismic observation of volcanoes). We also installed 3 tiltmeters in April 14-17 around Usu volcano. Recording and analysis of tilt data have been conducted at Usu Volcano Observatory, Hokkaido University.

GPS: To observe the deformation in and around the Usu Volcano dual frequency GPS receivers were deployed at six sites whose averaged baseline length is about 5km. Our institute collaborated with Hokkaido University, Tohoku University, Nagoya University and Kyushu University in this operation. To detect deformation of the volcano every day we construct the automatic analysis system of the GPS data with Hokkaido University. This system get the GPS data every 6 hours using a mobile phone, then calculate the deformation with Bernese GPS software Ver. 4.0 BPE. Finally, the figures of the time-series are upload on the Home Page of the Hokkaido University. We can detect about 20cm/month at the nearest site to the crater until the begging of May 2000 and deformation rate is decrease in middle May. It became possible that the position of the sites could get every several hours by this system.

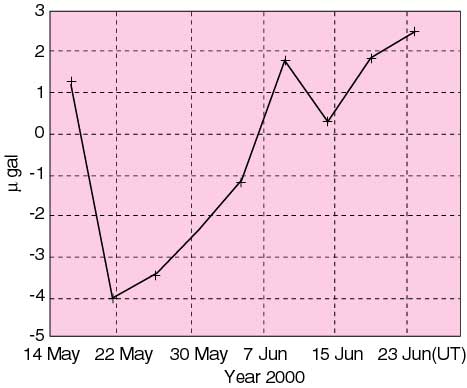

Gravity: After the eruption of 2000 Usu volcano, we carried out an absolute gravity measurement in conjunction with Hokkaido University for more than 1 month since 14 May, 2000; the site is only 2 km away from the eruption vent. Figure 2 clearly illustrates a gravity decrease until around 22 May, followed by an increasing trend; such a small but significant gravity change could never be detected until we used a high precision absolute gravimeter. The detected absolute gravity change is consistent with the changes in ground deformation measured around the Usu volcano.

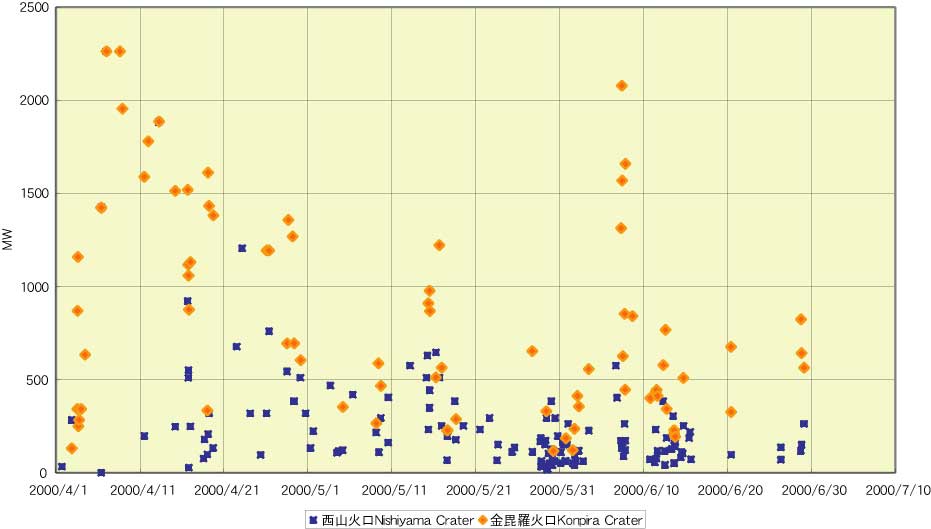

Geothermal observation: Heat discharge rate from the newly opened craters on the northwestern part of Usu Volcano is estimated by analyzing video images of the volcanic smoke as a part of the joint observation. The heat discharge rate was rather small at the beginning stage of the eruption, which has intermittent explosions, but increased rapidly on about April 7, which has continuous eruptions, and decreased gradually within one month. The amount of the heat discharge for 1-month from the beginning of the eruption is estimated about 2GW in average, which is 10 times of the discharge rate in the last eruption in 1977-78. The large discharge rate caused by the intense interaction of ground water and magma may make eruptions to finish in a short time. The fundamental research of analyzing the infrared imagery of the volcanic smoke was also done.

Time-differential stereoscopy observation: Volcanic deformation was tried to detect by digital photographs taken exactly at the same location. At Toyoura town about 15-16km west of the Nishiyama craters, it was possible to observe a part of the craters. Using a pair of photographs taken at this point after April 3, 2000, remarkable uplift more than 1 m per day was proved on April 4 around the craters by a time-differential stereoscopy. The uplift attained more than 10 m in total with gradual decrease in rate. Considering the direction of the uplift with southward shift of the ground surface, a certain amount of magma was suggested to intrude at a shallow depth beneath the middle of the Nishiyama craters.